GEORGE HARRISON

LIVING IN THE MATERIAL WORLD

Day 1

- Monday 2nd October 1972 -

Day 1

‘The Lord Loves the One

(That Loves the Lord)’

– Takes 1-23.

I wrote [the song] after Swami A. C. Bhaktivedanta1 came to my house one afternoon… Most of the world is fooling about, especially the people who think they control the world and the community. The presidents, the politicians, the military, etc., are all jerking about acting as if they are lord over their own domains. That’s basically problem one on the planet… Some people have thought that in certain songs like this one, I was giving them a telling-off or that I was implying that I was ‘holier than thou’.

I do not exclude myself and write a lot of things in order to make myself remember.

This is a key distinction: George is not necessarily preaching to the listener, but rather urging himself to stay on the spiritual path and encouraging those who seek that same path to do the same. It is evident, though, from listening to these sessions, that the making of this album was in no way akin to recording a series of dour ecclesiastical sermons. George had a small coterie of close friends around him for the recording of these personal, yet universal songs, and he sounds self-assured and happy in their company, the studio providing a place of creativity, familiarity, and sanctuary.

The level of Phil Spector’s involvement in the sessions has always been something of a mystery, with received wisdom (corroborated by the album credits) being that George had undertaken most of the production duties himself. Yet the session tapes reveal that Spector was indeed present for a lot of the tracking sessions, and he is often audible on the control room talkback microphone addressing George or the other musicians and directing proceedings alongside George. There are times, though, when George expresses frustration with Spector’s input, or lack of it, as well as his frequent interruptions during takes. Eventually, Spector would drop out due to, ‘personal problems and fatigue’, but there is evidence that even then he was keen to return to remix the album with George. However, his various issues – not least with British immigration – had clearly become too difficult and distracting for him, and too impactful on the progress of the record, so in the end George decided to complete the album himself.

I know in transitioning from that album [All Things Must Pass] to Living In the Material World, that it was a small rhythm section and [George] felt much more comfortable… When Phil started producing, they didn’t get on and I think that relationship had kind of just expired. And I’m sure that some of that was happening during the latter part of the All Things Must Pass sessions as well.

All of this, though, was yet to become apparent as the musicians, engineers, and production team of Harrison and Spector convened at Apple Studios in Savile Row to record George’s eagerly awaited follow-up to the lauded All Things Must Pass.

The setup for ‘The Lord Loves the One (That Loves the Lord)’ has Klaus’s bass on track 1, Jim’s drums on tracks 2 and 3, George’s acoustic guitar on track 5. The electronic piano played by Gary starts out on track 6 but is quickly moved to tracks 7 and 8, and George’s vocal is on track 10.

They start off with a couple of good, rough takes which have a faster tempo than the final version, but there’s already a good feel to the performance and a rather lively mood compared to the final released version. There is some discussion about the arrangement, with George suggesting a few changes to the band which they rehearse before another faster performance, take 3. George discusses what to do for an ending and mentions that they should fade out over a chorus, perhaps with a solo, ‘a bass solo!’, he jokes with Klaus, ‘or a sax solo!’. In fact, he will eventually decide to add the slide guitar solo which we hear on the final version. Spector suggests not having a fade out at all to which George replies with mock incredulity, ‘What, and have a real ending? I think I’d rather have it going out still moving, so it just fades out, but we’ll use that one on the stage version, (laughs) remember that!’

This method of running through the songs and rehearsing them together in the studio just before recording is slightly unusual, as most musicians would be conscious of the expense of using their precious studio recording time to rehearse, and so would arrive fully practiced and with the arrangement of the song fairly locked down. However, in George’s case, as an ex-Beatle with the luxury of his own record label and studio (at Apple) at his disposal, it makes more sense. It’s also testament to the musicians’ abilities, as well as George’s recently honed skills in musical direction and production, that they could create, arrange, and record these songs so quickly. Throughout the two weeks of tracking sessions, this would be the pattern. None of the musicians would have heard the pieces until just before they recorded them, though Gary Wright recalled George demoing some songs to him personally while they were on holiday together in Portugal a few months prior.

Jim, did I ever tell you how hard it was trying to edit the Bangladesh film? There were some bits trying to get you in sync, because you know when you were going, hitting the downbeat with your snare, you were doing, this hand was going like that, so you were going (makes a snare sound), and they were looking at it for days, trying to find… ‘It’s out of sync! And look, his hand’s up there, and I suddenly realised, ‘Oh, he must be doing a bit of a trick!

George’s, by this time extensive, experience in the studio is evident in his forward-thinking, even at this early stage of recording, about the overdubs to be added at a later stage. Having learned from past experience, he wants to avoid making the process more difficult for himself. After take 4, he says to Phil McDonald, ‘Phillip, remember on my other album [All Things Must Pass] you never recorded the voice thinking, ‘Oh he can dub it on later’, and it was just murder dubbing it on, so try and get the voice as if it’s the real one.’

Takes 10 to 16 are all faster than the released version and are played energetically, though only a couple are actually complete. At take 20, the tempo is significantly slowed to a more similar speed to that of the released album version. Take 22 is a bit shaky, but take 23 is better and is marked as ‘Good/Best’ and cut out to the master reel.

Day 2

- Tuesday 3rd October 1972 -

Day 2

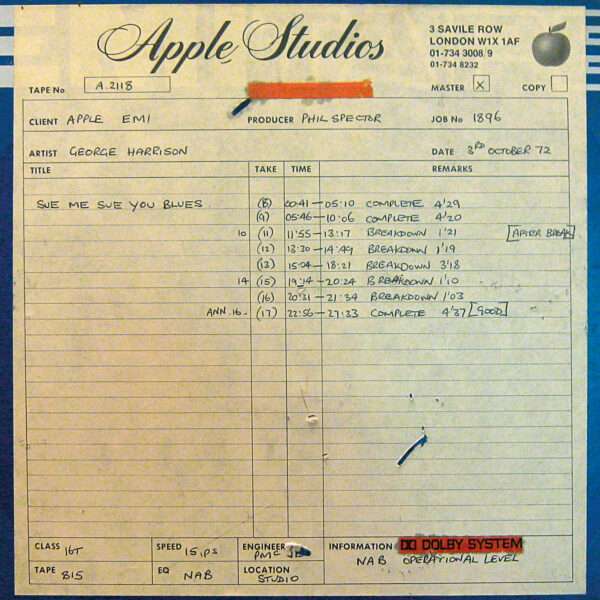

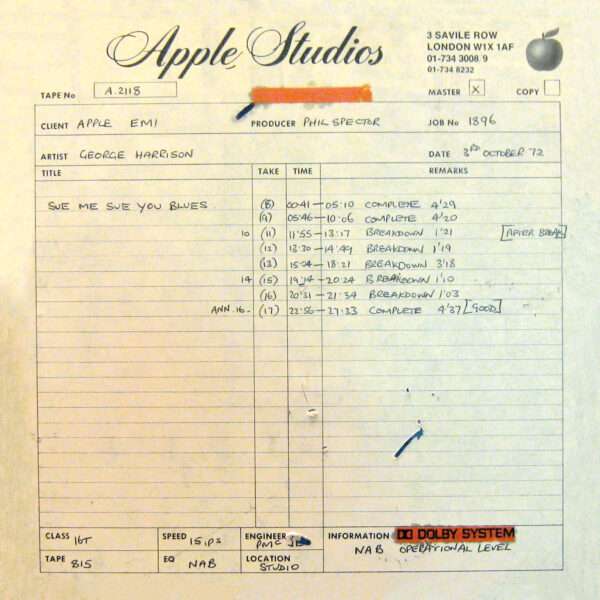

‘Sue Me, Sue You Blues’ – Takes 1-18.

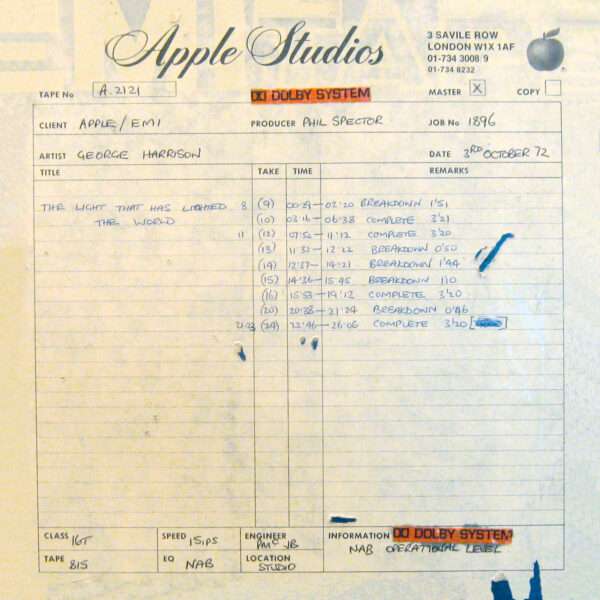

‘The Light That Has Lighted the World’

– Takes 1-34

‘Well, that’s another great example of George’s musicality. He always told me that ‘Sue Me, Sue You Blues’ – apart from the words being about lawyers, which is one of his favourite subjects – the groove and everything, and the phrasing of the song was kind of built around his version of a Ry Cooder kind of song… So, he wanted me to kind of play like what I would play with Ry and I… that never works for me… I can’t think like that, but I made him think that I was thinking like that, and so all I did was I just played the song, you know? I played the song the way I heard it and… and it was a little busier than I probably would normally have played but that was with his blessing and it’s one of my favourite things to listen to now. It’s just great. So, when I played with George, I felt like nothing could go wrong.’

‘Sue You, Sue Me Blues’ has similar instrumentation to ‘The Lord Loves the One (That Loves the Lord)’, with Klaus’s bass on track 1, Jim Keltner’s drums on tracks 2 & 3. George’s slide guitar/dobro is on track 5 with his voice also audible on that track. For the first take there is piano on tracks 7 & 8 although some subsequent takes only have piano on track 8 and from take 6 onwards there is electric organ on track 7 (Gary) and piano on track 8 (Nicky). George’s vocal is on track 10.

As with the previous song, the group use several takes to rehearse the song with the first three being fairly loose and at a faster tempo than the final version. By take 4 the tricky syncopated rhythm is really coming together, although they struggle to keep it consistent during the song. As George says at one point, ‘It’s hard with this tempo, it tends to always keep getting really fast.’ Takes 7, 8, and 9 are all very lively though, with only a partial vocal and none at all on take 9, but there is some great slide playing from George. After a break, things slow down a bit from takes 11-16 as they dial in the tempo used on the final take. Take 17 (announced as 16) is entirely instrumental and is marked on the box as ‘Good’, but it is take 18 which is marked as ‘Best’ and is cut out to the master reel.

Having the preferred take of ‘Sue You, Sue Me Blues’ in the can, the group embark upon a quick jam session with George leading them in an endearingly daft rendition of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’. This is followed by a fragment of ‘River Deep, Mountain High’ before George launches briefly into a jokey version of his own ‘The Light That Has Lighted the World’ followed by a bit of ‘Miss O’Dell’ in a ‘country-style’, listed as ‘Isabel’ on the tape box, with just tremolo electric guitar and a vocal.

The next song to be tracked is ‘The Light That Has Lighted the World’. The first take is in E, a lower key than the album version, which gives the song a markedly different feel. The arrangement has bass on track 1, drums on tracks 2 & 3, electric guitar on track 5 through a Leslie speaker, harmonium on track 6, piano on tracks 7 & 8, and George’s vocal on track 10. For the next take, however, they change key to G and the harmonium on track 6 is dropped, with Gary moving to an electric piano with added tape delay and echo on tracks 11 & 12. George also swaps his electric guitar for an acoustic on track 5, playing simple plucked arpeggios, however at the end of the take he says, ‘I’d prefer not to play at all Phil ‘cause I just can’t sort of think of singing and ding ding, ding ding [makes the sound of strumming the guitar]’, and in the subsequent takes George does indeed abandon the guitar completely to concentrate on his vocal.

The band continue to work on ‘The Light That Has Lighted the World’, with George tweaking the arrangement slightly as they go, though there are frequent breakdowns as the band forget the changes previously made. Takes 16 and 24 are complete, and 24 is even marked as ’Good’, although this was later scratched out. The next tape sees several partial takes which, although incomplete, are approaching the final arrangement of the song and George feels that, ‘All those beginning bits are good… I thought everybody up until where we keep breaking down, it seems perfect.’ The final takes 33 and 34 are both complete.

Day 3

- Wednesday 4th October 1972 -

Day 3

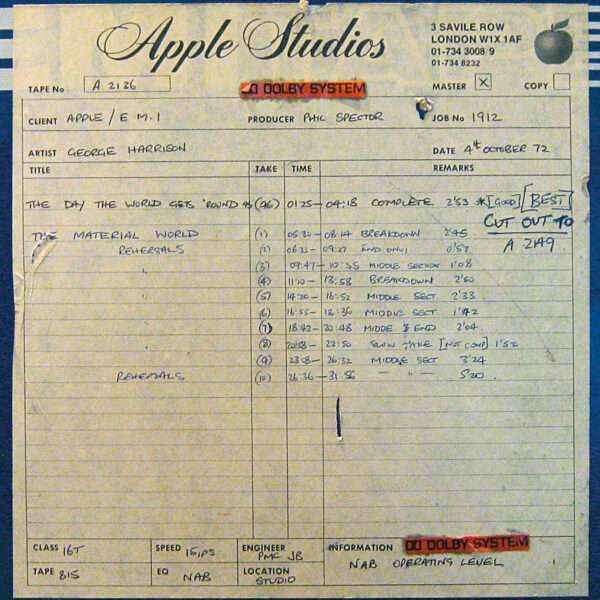

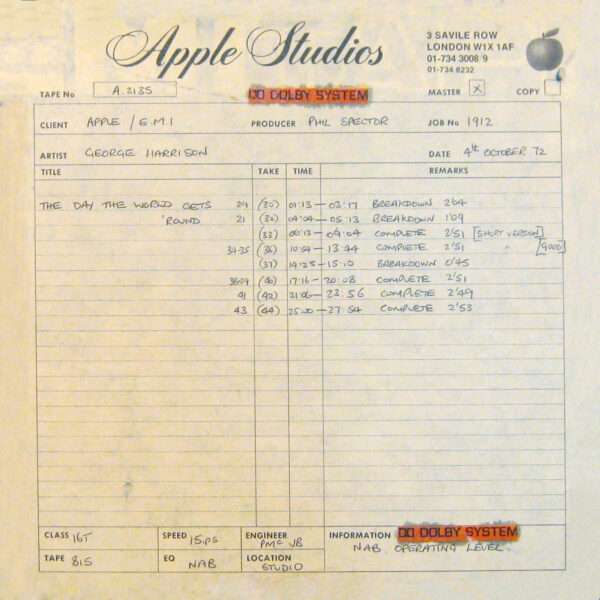

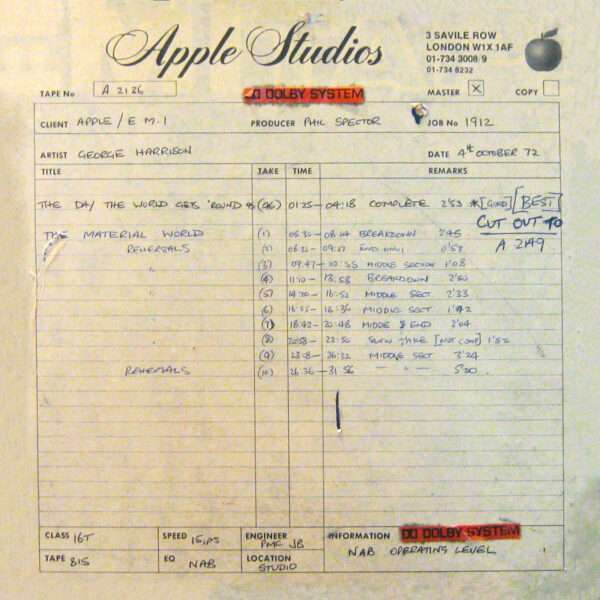

‘The Day The World Gets ‘Round’

– Takes 1-46

‘The Day The World Gets ‘Round’ is the next song to be tracked, and they start with a run-through so the band can get a feel for the tricky timings, with George calling out suggestions for the band as they go while singing a guide vocal, as he does on most of the following takes. The instrumentation features Klaus’s bass on track 1, drums on tracks 2, 3, and 4, stereo acoustic guitars on tracks 5 and 6 played by George with Pete Ham and Joey Molland of Badfinger, and possibly Tom Evans as well, although he is not mentioned when at one point George asks, ‘It would be good if… I don’t know if Pete and Joe are playing with me on that bit?’. Stereo piano is on tracks 7 and 8, and George’s vocal is on track 10. From take 5/6 onwards, a harmonium is added on track 12, playing a simple, almost drone-like part. At this point, there is still a 4-bar intro before the first line, but after the complete take 12, George suggests that they cut the intro to just one bar, and shortly after that, for take 18, George and Phil Spector discuss abbreviating this even further so that the song starts with just George’s vocal and the harmonics on guitar, as heard in the album version. The drums in these early takes enter later than in the final version, only appearing after the first verse. Take 22 has just the harmonium joining George after the first line before the pianos and bass come in after the second ‘The Day the world gets ‘round’, and the drums only join in on ‘Such foolishness in man’, emphasising the change.

George doesn’t quite seem to be happy with the bare arrangement of the introduction, saying, ‘Where is everybody? Is it only me now? Maybe [we should] go back to the big band version?’ So, for the next complete take (25), the drums come in sooner, alongside the piano and bass, and by take 26 everyone joins in unison after the first line, with George warning, ‘Yeah, everybody all in, but not heavy. Light at the beginning stages and heavy during the middle bit’. For the last few takes, George does not sing, other than the ‘Who bow before you’ section, but as the takes run into the forties, the arrangement and feel of the song approach the final version and take 44 is nearly there with George saying, ‘Yeah, OK, remember that one’. Take 46 is deemed to be ‘Good/Best’ and is cut out to the master reel, after which the musicians call it a day.

Day 5

- Friday 6th October 1972 -

Day 5

‘The Light That Has Lighted the World’

REMAKE – Rehearsals & Takes 1-34.

After a few silly interludes they try a new arrangement with Nicky alone playing a delicate intro on the piano, which he subtly varies each time they do a take. George then sings the first part of the verse with only Nicky’s piano accompaniment before the harmonium comes in on the line, ‘The thoughts in their heads’, and then everyone else joins in on the line, ‘So hateful of anyone that is happy or free’. Gary Wright says, ‘I don’t know if you think it’s too much, but on the harmonium, I’m trying to play in and out, sort of like strings would play, but if it’s too much then just tell me.’

Take 27 and 33 are both complete and 33 is listed as ‘Good’ on the tape box. In fact, Gary says just after the take, ‘That was good, we’ll get it on the next one’, and so it proves, with take 34 being marked as ‘Best’ and cut out to the master reel.

Day 6

- Monday 9th October 1972 -

Day 6

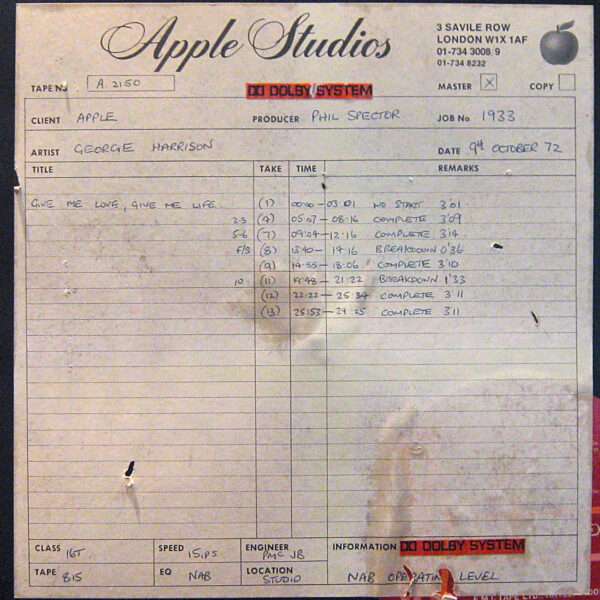

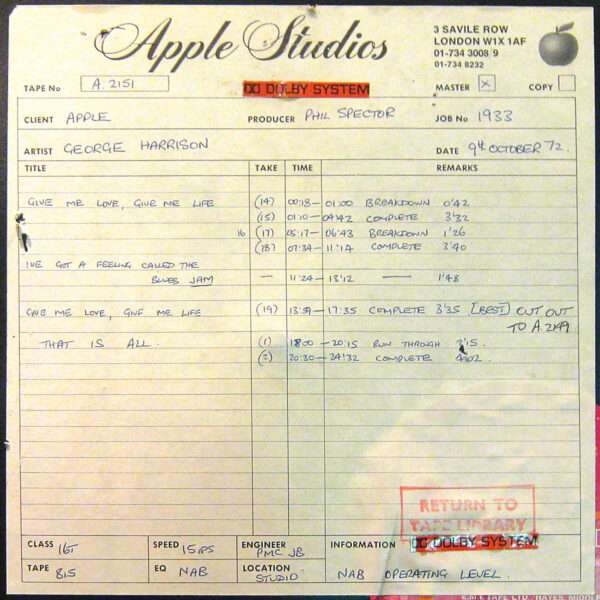

‘Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth)’

– Takes 1-19.

‘That Is All’ – Takes 1-32.

After the ‘weekend off’, when we know that in fact work continued at Apple Studios on Nicky Hopkins’ The Tin Man Was A Dreamer album for some of the musicians, the next track to be recorded is ‘Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth)’. As before, there are several loose rehearsals where they are all working out their parts and experimenting with the arrangement of the song. It’s a simple line-up for the basic track with Klaus on track 1, Jim’s drums on tracks 2 & 3, George’s acoustic guitar on track 5, stereo piano on tracks 7 and 8, George’s vocal on track 10 and stereo harmonium on tracks 11 and 12. After a few incomplete takes, just before take 11 George suggests a variation of the Hare Krishna Maha-mantra chant, ‘All together, Harry Nilsson, Harry Nilsson, Nilsson Nilsson, Harry Harry!’ and quips, ‘Son of Tambourine Man!’.

Takes 12, 13 and 15 are all complete, though both Jim and Klaus are still trying to find the right part to play with the tricky syncopated rhythm.

“‘Give Me Love’ is a very, very hard song to play. It’s this mixture of a rock beat, against a swing beat. Maybe I get too personal about the music now. Because that’s a very hard thing to do, and Jim and I are sort of really, very special for this, and that really worked – to me, it worked wonderful. I play a lot of notes on the bass, and they kind of flow along and George is playing his acoustic guitar. This is the basis of the song.”

After a short rendition of Hank Williams’ ‘Lovesick Blues’ (marked as ‘I’ve Got A Feeling Called the Blues’ on the box), they get the master performance with take 19 and move on to a song with a very different feel, ‘That Is All’. The band run through the song a couple of times, and it starts off with Klaus’s bass on track 1, drums on 2 and 3 and George’s electric guitar part on track 5. There are initially two pianos: Nicky Hopkins on tracks 7 and 8 as usual, and Gary Wright on tracks 11 and 12. Gary changes to a harpsichord towards the end of the first run through and asks afterwards, ‘Does it sound OK with two pianos, or should I move to organ or…?’. Spector asks to hear the track again and so Gary alternates between the piano and harpsichord on the second run through as well.

Throughout the album, Gary experiments with various keyboard instruments including a harmonium, piano, electric pianos, and organs. Nicky mainly plays piano although he also plays harpsichord, probably a Baldwin electric model. There is no definitive list of the in-house instruments kept at Apple Studios, and indeed it seems that it was the norm to hire equipment when required, as indicated by a price list showing the equipment available to rent in January 1972, found in the Apple archives. It’s very likely that instruments from this list, including the Baldwin electronic harpsichord (a fairly rare instrument at the time), and the Wurlitzer electric piano, were used on the record.

Before take 10 of ‘That Is All’ there’s a change to the tracking of the instruments, and George’s electric guitar through a Leslie speaker swaps with Gary’s keyboard, moving to tracks 11 and 12, while Gary switches to a Fender Rhodes with tremolo on tracks 5 and 6. They continue with this setup through take 24, which is a complete take, before another brief jam in a jaunty circus-style during which Gary reverts to the harpsichord, which he continues to use on subsequent takes of ‘That Is All’. They work on the arrangement through takes 25 and 26 before launching into an impromptu rendition of ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’, after which one of the musicians asks George how he knows the words to these songs and George replies, ‘I just learn them by driving in the car and listening to the tape’.

Ultimately, although they manage several complete takes of ‘That Is All’ on the 9th, none are selected as being good enough for the album and so they call it a day after take 28.

Day 7

- Tuesday 10th October 1972 -

Day 7

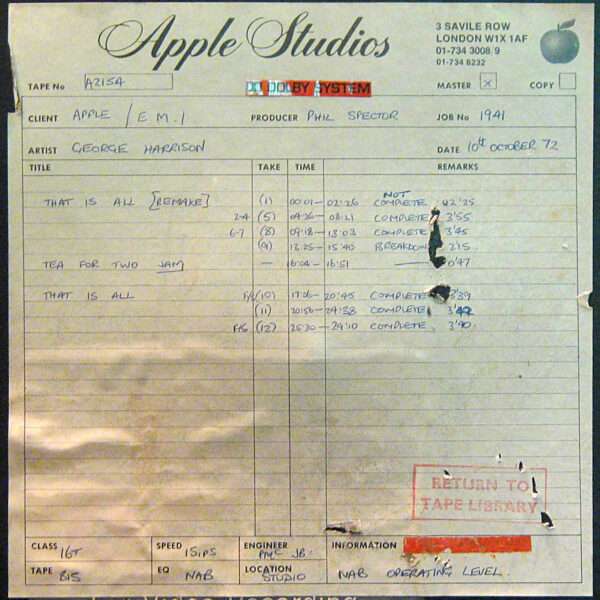

‘That Is All’

REMAKE – Takes 1-32.

George and the musicians return to the studio on the Tuesday and decide to remake ‘That Is All’ with a slightly different setup. Jim’s drums are now assigned to three tracks (2, 3, & 4). Stereo piano is on tracks 5 and 6, George’s electric guitar through a Leslie on 7 and 8 with his vocal on 10. Gary plays a Wurlitzer with tremolo on 11 and 12 and Nicky switches between piano and harpsichord on 15 and 16. After the complete take 8 the song is really coming together and George even comments that, ‘It feels nice now, I don’t know if it’s gelling in the box?’. There is a brief, spontaneous jam on ‘Tea for Two’ before the next round of takes. After the complete take 11, Jim Keltner asks George, ‘Is there space for a guitar solo? It [would be] really nice’, and George replies, ‘Only on the second bridge… But I could make one of the verses into it’. As it turns out, George does later overdub a guitar solo at that point in the song. Take 31 is selected as ‘Best’ and is cut out to the master reel. Take 32 is also complete and George even says afterwards, ‘That one really felt good!’.

Day 9

- Thursday 12th October 1972 -

Day 9

‘Be Here Now’

– Takes 1-19.

Recording of the next song to be tracked, ‘Be Here Now’, continues on the same tape from which the master take of ‘Don’t Let Me Wait Too Long’ had been cut out the previous day. Ringo and the members of Badfinger are not part of the day’s session, and Phil Spector is also not in attendance.

‘A lot of the time, most people are either dreaming about tomorrow – the future – or ‘Oh, wasn’t it good last week?’ But, in the meantime, they’re not having that experience of what’s happening now. So, I wrote that from that idea: ‘Remember, now, be here now / As it’s not like it was before / The past, was, be here now.’

Klaus is on track 1 as usual but playing an upright acoustic bass this time. Jim’s drums are on tracks 2 and 3 and George’s acoustic guitar is on track 6. Nicky’s piano is assigned to tracks 7 and 8, with Gary’s harmonium drone on track 9 and George’s vocal on track 10. The musicians seem to have rehearsed the song a few times before recording commenced as Gary can be heard asking George about how he had ended the song ‘last time’. After one complete run-through where parts are still being worked out and George is calling out the changes, surprisingly the second take of the day is marked as the ‘Best’ and is cut out to the master reel.

Although they already have what will become the master take, the tracking continues on a fresh tape, and they will record 19 takes in total, only three of which are complete. There is a slight change to the recording setup for this tape with the organ assigned two tracks (11 and 12), which, combined with the echo, really heightens the hymnal feel of the song. Takes 3 to 7 are all incomplete and there is a lot of chat about headphone levels and the volume of the harmonium. George is concerned whether the subtle hammer-on/pull-off guitar riff will be picked up by the microphones properly and is also struggling to hear his own voice in the headphones, complaining that, ‘I’ve got to take me earphones off to hear if I’m singing in tune’. In fact, after the complete take 8, he says, ‘I think I’ll try one without the earphones’. Take 11 is complete, but George says that he didn’t like it, so they go for a few more. After take 12 George asks for the echo to be taken off his guitar and wonders whether they are now playing it too slowly. Take 14 is complete, and for the first time Jim marks the time on hi-hat on the ‘It’s not what it was before’ sections. It’s another beautiful take, with Gary asking afterwards, ‘Were there any goofs in that one? It sounded good.’

‘The time signatures in ‘Be Here Now’ are incredible. That’s one of those tracks that (George) had where he’s mixing time signatures, to make it really unusual. It’s very Indian sounding in that respect. And it also is reminiscent of a little bit of ‘We were talking about the space between us’ from Sgt. Pepper, in so much as it’s like this drone kind of chord. That whole idea – Be Here Now – I don’t know whether you remember Baba Ram Das – but he had that book, called Be Here Now, and that was a really popular book, in the late Sixties, early Seventies – that everybody who was into the spiritual movement was reading. But it was just that whole idea of being in the present, of being present in the moment, living in the moment.’

From take 15 onwards Klaus varies his bass part on the ‘It’s not what it was before’ refrain, moving from the D up to an E rather than descending to the C# as he had initially, which gives a remarkably different, somehow more optimistic feel to the song. Nicky too continually makes exquisite variations to his mellifluous piano part, subtly altering the feel of each take. Before take 16 Jim decides to abandon his marking time experiment and returns to the sparser playing of the earlier takes. Take 18 breaks down, but afterwards Klaus tells George that, ‘the singing sounds fantastic, sounds really great’ and Gary agrees, ‘Yeah the singing’s really good’, to which George modestly replies, ‘Is it? Well, that’s… I don’t know’.

They start a new tape for the final take, 19 which has a lovely feel. Afterwards Gary asks, ‘Can we hear some of these to see if it’s getting anywhere? Or do you want to do some more?’, and George says, ‘That one felt quite good, I just blew that bit on the end there’. They seem to agree that they have what they need, and George will go on to add various overdubs to take 2 to create the finished master.

Day 10

- Friday 13th October 1972 -

Day 10

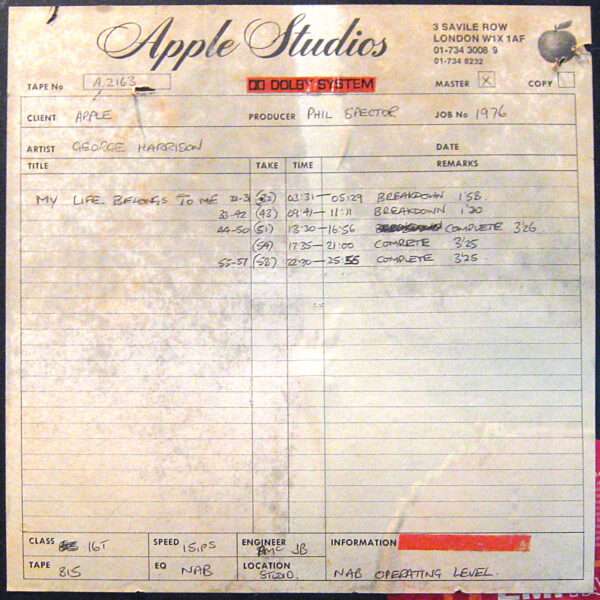

‘Who Can See It’

– Takes 1-94

‘Who Can See It’ (listed as ‘My Life Belongs to Me’ on the box) is next to be recorded, continuing on the same tape as the final ‘Be Here Now’ take. Phil Spector is back in the control room and is frequently heard in between takes addressing the musicians over the talk-back microphone.

Klaus is on track 1, back on electric bass, and Jim’s drums are on tracks 2 and 3. George’s electric guitar through a Leslie cabinet is on tracks 5 and 6 (bass rotor on 5 and treble rotor on 6); Nicky’s piano on 7 and 8; George’s vocal is on track 10 and Gary is playing organ on tracks 11 and 12. They spend a few minutes trying to work out how best to start the song and Phil Spector can be heard back in the control room contributing ideas. He and George debate how much of the chorus to use as the intro and they have a couple more run throughs before George calls out, ‘Night at the Opera, take 1’. Spector laughs, saying, ‘Phantom of the Opera, that’s what it is!’.

After making it through the first complete take, there’s a jokey jam of ‘Let’s Go To The Hop’ before returning to ‘Who Can See It’, and Gary is moved to the harmonium which is recorded on track 11. After a couple of false starts George wonders, ‘Couldn’t it be done like, almost stopping each time?’, referring to the halting breath in the timing after each line, and they incorporate that into the next take (21). ‘What a nice song!’, George declares afterwards.

The band keep rehearsing and working on the song through another 25 or so takes. There are lots of false starts and breakdowns, mainly due to the tricky timing and the entry of different instruments, to the point that George quips, ‘I can’t wait to hear the cover version of this one!’ By this point the takes number into the fifties, though most have been fairly brief, incomplete attempts. Takes 51, 54 and 58 are all complete, and although there are a few issues, the players are beginning to gel and find the feel for the song, albeit the performances are generally faster than the released version. After take 58 they stop for a break to listen to some playbacks of what they’ve been doing as George notes, ‘It mightn’t be anything like it should be anyway.’

Back after their breather, there’s a brief rendition of ‘Masterpiece’ by Bob Dylan and The Band (which had only been recorded by Dylan the previous year) to warm up and then it is straight into more takes of ‘Who Can See It’ on a fresh tape. George may not quite have all the lyrics yet, but his voice sounds strong, and he is really committed to singing most of the song for the majority of the takes. He even quips that, ‘Jimmy Young would do that one good’.

By take 71 they are really getting into the song and bar the occasional mistake it is sounding good. After the take, George says, ‘That one felt OK’, but Jim asks for one more. Take 73 is also excellent, but George thinks ‘the end went a bit dodgy’. He doesn’t seem to be too weary though from what is turning into a long session, saying, ‘Yeah, I’ll do it more and more’. Takes 76 and 77 are also complete and are very close to the final, released version, so much so that on the final line of take 78 George sings, ‘My life belongs to one more take’. Unfortunately, more false starts and breakdowns ensue, and after one where Jim makes a mistake and quickly apologises, George sweetly consoles him saying, ‘It’s all right, Jimmy.’ As they enter the nineties there’s a couple of complete takes (91 and 93) which are faster than the final one, but the performances are great and George knows they are close, exclaiming, ‘Could it be?’ after take 91. It’s not, but they slow things down considerably for take 93, and in fact, it’s take 94 which is marked as the best one and cut out to the master reel for overdubs.

This marks the end of the main body of the tracking sessions, and work on the album does not resume until the 23rd of October when the overdubbing phase begins.

Day 12

- Tuesday 24th October 1972 -

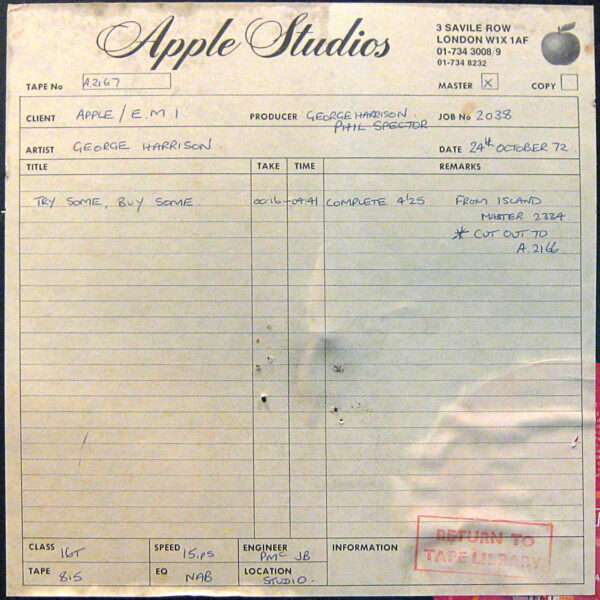

Day 12

‘Try Some, Buy Some’

16 track to 16 track dub with overdub.

One of only two songs on the album not to come from the first two weeks of tracking sessions, the 16-track master tape for ‘Try Some, Buy Some’ is dated 24th October 1972 and it has a telling note on the label that it is a copy ‘From Island Master 2334’. That tape is also in the archive and dates from the sessions in February 1971 for a prospective Ronnie Spector album which George co-produced with Phil Spector. The album never came to pass, but ‘Try Some, Buy Some’ was released as a single on Apple records, backed with ‘Tandoori Chicken’. The sixteen-track master tape for the single was created on 5th March 1971 at Island Studios in London from the original eight-track tape recorded at Abbey Road, and it was that sixteen-track tape which George used as the basis for his version of the song and therefore the Living in the Material World version too. John Barham, the composer of the orchestral arrangements for the Ronnie Spector version of the song, confirmed that the string and brass parts and other overdubs were added at Island Studios in Notting Hill Gate in London. To create George’s version, on this day the tracks from the single master created at Island are copied to a fresh 2-inch 16 track tape but the tracks are moved around to match the order of tracks used for the recent tracking sessions for the album, presumably to make mixing a little easier. This copy was then cut out to the multitrack master reel for the album, but it’s worth noting that this means that the tracks carried over from the Ronnie Spector version of the song are already a third generation copy of the original tracks which, combined with a different mix, helps explain why this version of the song doesn’t sound quite as clear as the Ronnie Spector single version.

Day 15

- Friday 27th October 1972 -

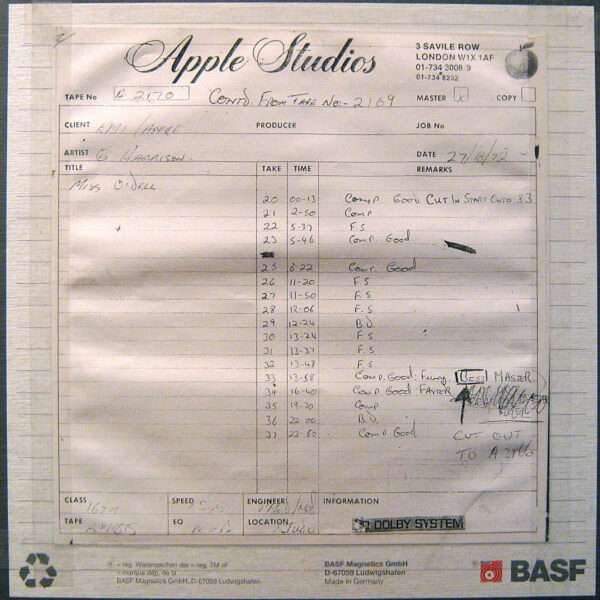

Day 15

‘Miss O’Dell’

– Takes 1-37

After a couple of days of overdubbing work, George returns to Apple Studios on the last Friday of October 1972, to record a song he had written the year previously whilst staying in Los Angeles, about former Apple employee, Chris O’Dell. This is not a full group session and features only George on 12-string acoustic guitar, Jim Keltner on drums and Klaus Voormann on bass guitar, although at the top of the first complete take (2) George does joke that, ‘We’re going to overdub the Pifco massager on top’. There is no sign that Phil Spector was present in the studio for this session.

Take 2 is a solid run through which sees Jim experimenting with a few fills and rolls and Klaus adding his walking bass line. George seems pleased, saying, ‘I like that ‘ringing on my bell’ ding-ding-ding’, and wonders if they should, ‘insert an extra verse length after the bridge, as a solo, and sing the last verse after that?’.

They do indeed try this structure out in the next take with George scat-singing through bits of the proposed solo.

Take 8 is the next complete take and at this point they try a new intro featuring the descending melody played by George and Klaus (as heard on the single version which was the B-side to ‘Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)’), although the cowbell which precedes it on that version is absent. Take 9 and 10 are also complete, but at this point the song still has a simpler, ‘straighter’ feel than the final version. They take a short break after take 10 and George can be heard discussing the bass line with Klaus before they carry on. Takes 11 & 12 break down, but Jim starts to play around with the percussion to punctuate and emphasise George’s vocal, weaving in and out of his rhythm guitar. Take 13 continues in that vein, but with a slower tempo than the album version, and Jim is enjoying himself, saying, ‘Well that was fun anyway!’ at the end of the take, and asking engineer Phil McDonald, ‘Are you getting too much cowbell Phil?’

After take 16 breaks down, Jim and Klaus seem not to be content with what they are doing, with both telling George that they aren’t sure what to play on this quirky song, and Jim asking whether to play ‘half-time or double-time?’ George reassures them saying, ‘Oh, don’t be ‘sure’, just do it!’. A new tape starts with take 20 which has a lovely, easy feel to it, and the musicians have by now settled into their parts, so there are several complete takes in a row, all with a similar vibe. There is a note on the box next to take 20 saying, ‘Good. Cut in start onto 33’, indicating that the intro from this take was actually combined with take 33, which is selected as the master take, to create the finished version of the song. Takes 23 and 25 are also marked as ‘Good’ and just before take 25 starts, off the cuff Jim plays the beat with the cowbell riff we hear at the start of the final version. George likes what he hears, saying, ‘That’s nice, you start it this time’, and they adopt that intro for the remaining takes. There are a few more false starts and breakdowns before take 33 which is marked, ‘Comp. Good. Funny. BEST’ and is cut out to the master reel for overdubs. Take 34 remains on the session reel and is also marked ‘Good. Faster’ though it isn’t significantly different to the previous take. Both takes 35 and 37 are also complete versions of the song and on the last one George asks Jim to make it a little bit slower, but they have what they need and after take 37 George says, ‘I think that’s quite enough of that one’, thus bringing the tracking sessions for the album to an end.

Notes by Don Fleming and Richard Radford

The session information is based on the original Living in the Material World production notes,

photographs and reel-to-reel session tapes in the George Harrison Archive.

The Living in the Material World session tapes created in 1972 and 1973 include

forty-two 2″ sixteen-track tapes, and eighty-two 1/4″ stereo tapes.

The chronology of the making of Living in the Material World is derived from the engineer’s

information on the tape boxes and Jim Keltner’s recording diary.

The multi-track and stereo tapes were transferred to 192 KHz/24bit digital preservation copies from the original analogue tapes by Matthew Cocker, Richard Barrie, and Paul Hicks, overseen by Richard Radford.